I staggered through a swathe of tangled shrub, fatigue eating my legs as I swerved the trunks of giant red cedars and peered into the dense mass of green and brown. The soles of my feet brushed the debris of dead plants, crunched on twigs and hit the exposed root of a tree. I fell forward, landing face down in damp earth that pressed into my lips and teeth. Pain rolled through my arms, hips and legs, and I needed a moment to lay still and take a long inward breath. Then I rolled onto my side and spat out the dirt, sat up and looked back into the forest. I saw no-one but I could hear the bodies moving between trees, fanned out to both sides and coming closer.

There was a voice, then another, speaking words I couldn’t hear but conveying a quiet fury that I could feel. They were not going to give up the hunt. I got back to my feet and took another deep breath. My tunic stuck to the sweat on my back, chest and thighs, and I felt the buzzing of tiny wings around my ears and eyes. A brief shrieking of birds around the treetops planted a wild thought in my head that they were calling to the hunters, telling them where I could be found. I was still short of breath but couldn’t stand still, and pushed forward again, kicking through vegetation as I ran blindly into the woods.

There was a voice, then another, speaking words I couldn’t hear but conveying a quiet fury that I could feel. They were not going to give up the hunt. I got back to my feet and took another deep breath. My tunic stuck to the sweat on my back, chest and thighs, and I felt the buzzing of tiny wings around my ears and eyes. A brief shrieking of birds around the treetops planted a wild thought in my head that they were calling to the hunters, telling them where I could be found. I was still short of breath but couldn’t stand still, and pushed forward again, kicking through vegetation as I ran blindly into the woods.

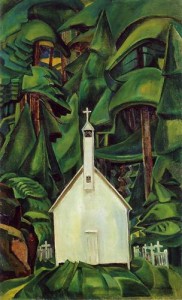

Over a hundred yards or so I dodged between trees, seeing only the mingling of bark and moss above the carpet of shrub. But then came a flash of white in one of the gaps, then an opening a few feet to its left that showed a longer stretch of scrub, then a clearing between the trees. As I moved into the space a large white shape appeared, and I saw that fifty feet away, nestled against the next wall of trees, was a church. It was small, just a few feet wide and not much longer, built from wood and painted brilliant white. A steeple was fixed to the front of its slanted roof, with an opening to a tiny belfry and topped by a crucifix. To either side was a collection of white wooden crosses planted in the earth and surrounded by a white picket fence. Little natural light reached the building – trees leaned over it from the back and sides and threw a heavy canopy between the roof and daylight – but the layer of white timber almost glowed against the dark density of the cedars. I had stumbled onto a source of Christian light in a place where the natives still ruled, and as I heard the hunters behind me I suddenly found hope in the thought of sanctuary. I ran towards the church, pressed myself against the wall beside the door and saw there was no lock, just a handle fixed to a latch. I offered a one second prayer and turned the handle. It was open. I stepped inside, closed the door behind me, staggered into the aisle and fell to my knees.

I placed my forehead against the floor and breathed deeply, the smell of the forest earth now replaced by the dry tang of timber. Again I felt the tunic hugging my sweat, but as my breathing levelled I realised that I could hear nothing from outside. I raised my head and looked down the aisle, seeing a table draped in cloth and topped with a small wooden cross, alongside which was the rough shape of a jug and small cup on a tray. Five rows of pews stood to each side, seating for no more than thirty people, and the only window was behind me, above the door and below the steeple. It was small but allowed a bold ray of light cover the altar and make it possible to see around the church. I didn’t know if I would be safe, but thought that the natives must have allowed someone to build the church and might respect it as a place that should not be invaded. I peered into the corners behind the altar and saw nothing, thought to myself that the place was empty, then heard a noise from behind. I looked around and saw a figure in the shadow of a corner.

“You’re fearful. You must be in danger.”

It was a male voice, clear but tinged by the accent of the natives. I didn’t know if he would be a friend or enemy, and as he stepped out of the shadows I stood, fists balled and arms tensed against the possibility of attack. As he come closer I saw that he was short but solidly built, with a square jaw and large eyes that dipped towards the bridge of a broad nose. His skin was pale brown, but as he emerged from the shadow I noticed a crucifix on a chain around his neck.

“You’re right,” I said. “Are you the priest for this church?”

“You can see the answer on my chest.”

The crucifix looked like many I had seen, but it didn’t provide the assurance that I craved. I also noticed the decoration that hung from a length of twine on both sides of his chest, miniatures of the masks I had seen on the native’s totems, faces that scowled and grimaced with aggression. He could as easily be one of the natives’ holy men.

“What is this place?” I asked. “I’ve heard no talk of it.”

“It’s a place for your people, and the natives; those who need a certain type of solace.”

“And sanctuary?”

“Sanctuary from who?”

“From the men who want to kill me.”

“Sit down, and explain.”

He gestured towards the first pew. I was still wary, but exhausted and desperate for a guardian, and placed myself on the seat. The priest went to the far edge of the pew, momentarily faded into the shadow, then re-emerged with a jug of water and a cup. He poured, I drank, he filled it again then sat beside me, placing the jug between us. I glanced towards the door, fearing the hunters could burst in, but realised that I could hear only the sounds from inside the church. The priest spoke again.

“You fear they’re outside.”

“They were closing on me. They must know this place.”

“Maybe, but they will not enter.”

“They respect its sanctity?”

“They respect anything rooted in the forest. Why are they hunting you?”

I hesitated. In the panic of fleeing the scene I hadn’t yet acknowledged what I had done, but in a few breaths I realised that I couldn’t hide the truth.

“I killed.”

“Why?”

“A woman. She had been deserted before we met. I loved her and she said she would be mine, but then the man who had first claimed her returned, and she returned to him. I was angry, humiliated and wanted revenge. I crept upon them in the night with my knife drawn, ready to kill the man.”

I paused and looked down, still breathing hard, held back by the pain of recalling something terrible. The priest touched my arm. I raised my eyes to meet his, fixed by a clear, penetrating gaze that didn’t console or accuse, but demanded truth.

“They awoke. My first thrust of the knife wounded the man. He was disabled, the second would have killed him, but she got between us. The knife pierced her heart. She died in my arms, whispering the other man’s name.”

I looked down and placed fingers on my chest.

“This is her blood, her death upon me.”

The priest looked at my hand. I realised that, while the blood on my tunic had dried, there were also patches on my fingers and palm. I raised the hand and pressed it to my lips, tasting the blood with my tongue. It drew the first tear since she had died.

We sat in silence for a while, long enough for the first wave of grief to subside. At first the priest kept his eyes on me without conveying any feeling, but then a hint of sympathy appeared in his face and he placed his hands upon mine and guided them to rest on my lap.

“So they hunt you for revenge, and you are fearful.”

“I don’t want to die. I’ve committed a terrible crime, but I’m not ready to face death.”

“And you seek protection.”

“This is a Christian church. I’m seeking sanctuary.”

He looked into my eyes, taking a few seconds to interrogate me through a gaze, then spoke softly.

“I can offer a moment of respite.”

He stood and walked to the altar, moved an object I hadn’t noticed on the tray, took the jug and filled the cup. Then he beckoned me to follow. I moved slowly, seeing that he held a plate in one hand and realising this was an offer of communion. I was surprised that this was the priority of a priest dealing with a self-confessed murderer, but decided that maybe it was a test of my faith, a step in assessing whether I was worthy of sanctuary. The priest dipped his head and I kneeled before him. As he held the plate before me I could see it contained rough circles of a dark dough, not the thin slivers of bread I knew from the few times I had entered a church. I let him place one on my tongue, felt a coarse texture and an unpleasant earthy taste, then pressed it against my upper teeth, took two bites and swallowed. Then he offered the cup that contained a pale liquid with a red tint.

“There’s no wine here,” the priest said. “I’m sure your faith can accept this as the blood.”

I sipped. It had a thin taste of sour berries and I couldn’t imagine anyone drinking it for pleasure. Maybe this was a more genuine communion, demanding a few seconds of discomfort for Christ. The priest placed the cup on the altar, paused as I absorbed the aftertaste of the liquid, then placed a hand on my head. I expected words in English, maybe Latin, but instead he chanted softly in a tongue that was similar but not identical to those of the natives. I listened for words that I recognised but heard nothing. This was a church that belonged to the forest. Then he told me to stand.

“You’re looking for sanctuary,” he said.

“I want to live. It’s my only chance.”

“And you believe you will it find it here.”

“It’s a church. In Christian countries it is a place of sanctuary, no matter what the crime.”

For a moment the priest was silent, his eyes fixed on mine, his expression now hard but without anger. When he spoke it was softly, but with a stronger sense of authority.

“If you stay here they will not enter, and I can provide you with water and food. But you would have to stay here. There would be no safe passage to another place. You would have sanctuary, but you would also be imprisoned.”

“But I would be alive.”

“Alive in this place. Look around. You see because for now the light comes through the window, but when the sun goes down there is just darkness. You can walk only a few feet in any direction. You can sit on a pew, kneel before the altar, contemplate God, but you cannot live. A church is built for moments of prayer and reflection, not for an escape.”

“You’re saying I have no escape?”

“Not within this place. The only escape is outside.”

“But I can’t get away from those who are hunting me.”

“You’ve taken a first step. You’ve acknowledged your crime.”

He kept his eyes on mine and his expression softened into the hint of a smile. I was frightened by what he had said, but also felt a vague sense of comfort. He was pointing towards where I could find a real sanctuary.

“You can take some time here,” he said. “As long you need.”

He took my hand and guided me back to a pew, and as I sat and faced the altar he moved away, his footsteps taking the path back to the corner where he had appeared. I sat with my head dipped, hands squeezed together on my lap, no words in my head but a feeling of surrendering myself to God, the forest, whatever waited for me outside. After a time I lifted my head, acknowledged the crucifix on the table, stood and turned into the aisle. I looked into the corner but couldn’t see the figure of the priest. I spoke.

“I’ll leave now. Thank you.”

There was no reply. I walked towards the door, stepped outside and moved forward into the clearing. As I stopped I could hear the sounds resume, a faint buzzing of insects, the squawking of birds above the trees, the crunching of twigs and growl of voices in the trees. As I waited the fear stirred again, responding to the anger I could sense blowing through the trees. I tried to resist, grasping at the priest’s words about the source of sanctuary, then thought of running back to the church. I turned, expecting to see the white steeple within the picket fence, and saw only the dense green and brown of the forest. Nothing.

As the voices came closer behind me I didn’t run or turn to face them. I just waited, feeling the tunic against my sweat, the insects in my face, the sense of immersion in the primeval forces of the surrounding forest. The voices stopped but the crunch of feet on twigs came closer. I could hear breathing, a final murmur in the native tongue, then a breath hot against the back of my neck. The fall of the axe brought my final relief.

(Inspired by Emily Carr’s painting, Indian Church.)