He must have heard the woman at the counter speak my name. As she passed me the bag of paperbacks a voice came from over my shoulder.

“I know you.”

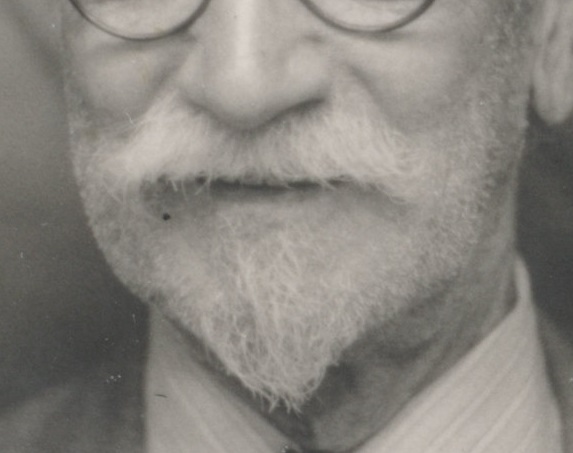

I looked around to see a male face, over sixty, thin and pale with round glasses, a grey beard and a few strands of hair combed back from the upper forehead. I peered for a moment without a making a connection, then he spoke again.

“Millworth Primary School. I think you were there about twenty years ago.”

Then I recognised him. There had been a thicker beard and more colour in the face when I knew it, but also a familiar gap in the front teeth, a mole beside the left nostril and a childish gleam in the eyes.

“Mr Bishop, isn’t it?”

“You remember me.”

“I can remember most of my teachers. But I’m surprised you remember me. I must have been one among thousands of kids.”

“Good to see you.”

I nodded, realised that a woman was behind him in the queue and stepped aside. I thought it would give me an opening to move away quickly as he was served, but instead he also took a sideways step and told the woman she could go first. I would have to talk.

“I see you have the reading habit,” he said. “What’s in the bag?”

“That Salman Rushdie book, a biography of Frank Capra and a Barbara Vine novel. I’ve got catholic tastes.”

“I’m impressed. I always rated you as one of the bright ones. I think I told you that.”

I remembered that he had, a couple of times, but that was just part of it.

“So what are you doing with yourself now?”

I told him that I was a business writer. He said he was impressed, that it sounded interesting, but asked if I had other ambitions. I didn’t feel like telling him that I was writing a novel in the evenings.

“I’ll see,” I replied. “It might open up some other opportunities over time.”

“Do you have a family?”

“I live with my girlfriend.”

“Not married?”

“We’ve been living together for three months. We’ll give it some time.”

There was a brief raising of eyebrows that I suspected was disapproval. He was the type from his generation who would still think it was wrong. I noticed the woman customer move away from the counter and gestured to him it was free, but instead he moved further aside, inviting me to carry on talking. I wanted to get away but didn’t want to make it too obvious, so I made an effort to be polite.

“Are you still at the school?”

“I retired last year. Thirty years there, the last fifteen as deputy head.”

“Well done.”

The thought of him being given more authority disturbed me.

“The place must have changed,” I added.

“Everything changes to some degree.”

He smiled, and I guessed that he hadn’t approved of all those changes.

“I suppose the teaching methods are different.”

“There are some new ideas. We’ve all had to adapt, but some of us have found a balance between that and the old ways. We understand their value.”

I recalled how he did things, giving the class a little lecture, usually including a reference or two to Jesus, setting a task, then picking out a couple of examples to praise. I was often one of those. Then he would pick out a couple of others so he could berate nine-year-olds as lazy and stupid and a disgrace to the class.

“What about the kids? Are they very different?”

“Well there are more from ethnic minorities, but the usual mix of good and bad. Some are ready to learn, others don’t want to. It usually depends on whether they come from a good or bad family. Some of the parents instill bad attitudes and slovenly habits.”

“I suppose they’re often the ones who are struggling to get by.”

I remembered kids in our class who came to school in tatty clothes, who had free lunches but had to stand in a separate queue and wait until the rest of us had been served.

“Well that’s often an excuse,” he replied. “It’s seldom justified.”

That didn’t surprise me. I recalled the time one boy came to school in a V-neck pullover but no shirt and had been ripped to shreds in front of the class for looking such a mess. Remembering the confused shame on his face brought on a flicker of anger. I suppressed it.

“Is it harder to keep discipline?”

“It can be a challenge. There are some constraints on teachers.”

“Are they still as strong on religion these days?”

“It is a church school.” He held the smile, with an effort. “Although there has been a change in emphasis. Most of the younger teachers don’t give much time to The Bible.”

“Sign of the times.”

“That’s the case, although it’s one I haven’t welcomed.”

I remembered how he had been the most fervent in combining the religion with the discipline. Every rebuke and punishment involved telling the child that they had personally offended Jesus in their transgression.

“I remember you were always clear about what you believed.”

“Of course. It’s so important to instill the right values in children. It needs those reminders of what Jesus taught, little lessons on how to be a good person.”

It was a reminder alright, of one day when I was nine. A boy named Terry had squirted me with the orange squash from a defrosted Jubbly. I grabbed at him and ripped his shirt sleeve. He went crying to teacher. Then Mr Bishop decided that a physical assault and a torn short was a worse offence than an unprovoked squirt that left an orange stain on a collar. So Terry was quietly told not to do it again and I got the lecture in front of the class, about how we shouldn’t lose our tempers and Jesus had told us to turn the other cheek. Then he made me stand facing the wall in a corner until five minutes before the end of school, when I had to stand in front of everyone with hands pressed together and eyes closed while Mr Bishop fed me lines for a prayer about what a wicked child I had been and that I would beg God for forgiveness every night for a week. When I was allowed to open my eyes I saw the young faces, showing a scared relief that it hadn’t been them, but a couple with wide smirks. I felt three inches tall. Now I noticed the satisfaction on his face.

“It’s good to see someone like you, clearly getting on well in life. Do you go to church?”

I had been an atheist since the age of thirteen, but I decided against telling him.

“I have a relationship with God.”

His smile broadened.

“I’m pleased to hear that. How does it work?”

“Private prayer, contemplation, placing things in the context of what would please him. It’s given me a sense of peace, and provided some revelations.”

“That’s wonderful. Is there one you could mention?”

I returned his smile.

“I’ve reflected on those years at school, especially the one I spent in your class, and I came to this realisation ….”

I let it hang for a moment, enjoying the excitement in his eyes.

“He won’t allow you into His place. You’ll have to go downstairs. And you’ll spend eternity face down in a pile of shit with a red hot poker up your arse.”

He froze into an expression of open mouthed horror. I held the smile for a couple of seconds, said goodbye and turned away. When I reached the shop door I looked around and saw that he hadn’t moved, but remained rigid, staring into the vision I had just planted in his mind.

That was thirty years ago. I still enjoy the memory.