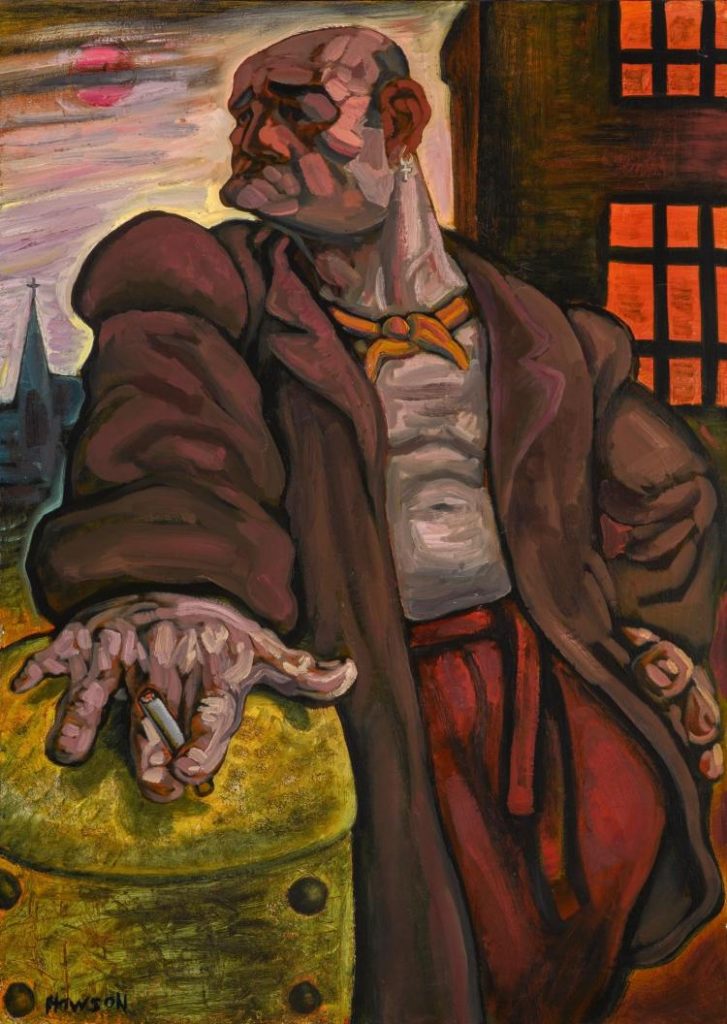

I didn’t know his name, just that everybody referred to him as the Noble Dosser. He always looked hard up, dressed in a shabby brown coat over a T-shirt or vest with a faded orange scarf around his neck, and clearly went days between shaves. But he was square jawed, upright, looked people in the eye and spoke with an air of self-assurance, free of shame about how he looked or where he stood in the world. People said he never lived anywhere for long – in and out of hostels, in bike sheds, on someone’s sofa, on a park bench – and he came and went from where we lived. I heard that he did labouring jobs around the city, worked hard and was usually reliable; but that every now and then he would go on a bender, that he had done nights in police cells and even a stretch in prison. There were people who did him favours – free meals, cash or a bed for the night – but he was always on the edge of things, a character who people knew without knowing much about him.

When I was a kid he would nod and smile, acknowledging that he recognised me. One time a mate said he looked like a dirty old man and I should stay away from him. I knew about dirty old men, had once been approached by one in a park, and could see the Dosser didn’t have the false smile and sinister glint in his eye. And when he saw me alone he never tried to take me out of sight, so I didn’t take it seriously and gave him a ‘Hullo’ the next time we met. On top of that, I was drawn to any adult man who showed an interest, probably because I didn’t have a dad. Well I had one, but he had disappeared when I was five and nobody seemed to miss him. Even as a kid I understood why, because I could remember he was always shouting – sometimes at me, more often at Mum – and ready to put his fist in her face. Mum’s family, neighbours and even Dad’s sister said we were better off when he disappeared, making good on his threat to go find another woman and have another kid. I didn’t miss him, but sometimes I missed having a dad, and was always glad when my uncle or a neighbour took me to watch football, or walk a dog, or just talk to me. It never went that far with the Dosser, but I always appreciated the nod and the smile.

I was fourteen that time there seemed to be more to it. It was a summer evening, walking home from the station with Mum after a visit to an aunt, when we saw him on a bench in the street with pie and chips and a bottle of Pepsi. He looked up, waited for us to come closer, and asked “How you doing?” I was surprised that he had spoken, especially when I realised the question was directed at Mum. She paused by the bench and said “We’re fine thanks. How about you?”

“I’m fine. A good feed, and I’ll have a roof over my head tonight.”

“Close by?”

“A few minutes’ walk.” He looked towards me. “You’re shooting up, on your way to being a man.”

I was stumped for a reply, then managed to blurt out my age.

“Any girls yet?”

I found an awkward smile.

“I wish.”

“I bet it won’t be long.”

He glanced at Mum and I realised there was something – a moment with eyes on each other and a faint smile hinting at a secret. Then she took her purse from her bag and removed a five-pound note.

“No, you shouldn’t,” he said.

“Don’t argue,” she said softly. “I know you can use it.”

He wiped his fingers on the chip paper, took the note and slipped it into his coat pocket.

“Thanks.”

“You’re welcome. We have to get home now.”

One more smile and we turned away. I was surprised as I had never seen her speak to him before; in fact I had never been with her when I had seen him. So I asked.

“Do you know him from somewhere?”

“Same as everyone knows him. He’s around here a lot.”

“Do you know his name?”

“No, but I know the name the people give him.”

Then she started talking about teatime, what was on telly that night and why I shouldn’t stay up late. I could tell she was a little flustered and thought again about the way they had looked each other.

That’s what put the idea into my mind, that there had been something between them before I was around, and maybe I was the result of it. Yes, I know Mum was married to Dad, but from what I had heard he was a monster before I was born. Maybe she had found some comfort with another man. I know most people would recoil from thinking that about their own mother, but I wouldn’t have blamed her. And the idea of the Noble Dosser being my dad was more attractive than the memory of the one I had known.

No, I didn’t ask her. A couple of times I mentioned our meeting with him, but she brushed it off and I guessed it would be a mistake to ask the question. I could understand, even with Dad long gone, why she should want to keep it secret. And the Noble Dosser drifted away. I might have seen him once or twice at a distance, but after a while people mentioned that he wasn’t around anymore.

It twenty-five years, before I saw him again. My father-in-law was in hospital, getting over what proved to be just a scare, and I was beside the bed sharing gossip and talking about football. An aunt, uncle and three cousins arrived, so I shuffled some chairs and moved to the edge of the group. An aimless glance down the aisle of the ward, and I spotted an old man alone, half upright in his bed. I couldn’t help a second look, noticing a square jaw on a worn out but familiar face. He turned his head, caught my eye and there was a moment of recognition. A lot older and frailer, but it was him.

I gave it half a minute of listening then said I had recognised someone, and walked towards the old man. He saw me coming, smiled and gave me the nod.

“Haven’t seen you for a long time,” I said.

“I drifted away from your part of town. Now I’m here.” His voice was weak, wheezy, but still calm and friendly.

I sat beside him. He seemed glad to have a visitor.

“What are you in here for?”

“Bits and pieces going wrong. Body’s falling apart inside.”

“I’m sorry. What are the doctors saying?”

“Not much, but I know they don’t have much hope.”

“I’m sorry.”

“I’m getting old. It happens.”

I placed hands on my knees and leaned forwards. I wondered if anyone at all was coming in to see him, felt a flicker of pity but guessed it wasn’t what he wanted. He spoke.

“Your mum still around?”

“Yeah. A few aches and pains but she’s doing OK.”

“Good woman. I liked her a lot.”

“I noticed.”

His eyes went deeper into mine, and I couldn’t help thinking there was something more to that familiarity. I felt the old question stirring.

“How well did you know her?”

He took a couple of quiet breaths and his mouth twisted into a smile.

“What has she told you?”

“About you? Nothing. But there was once when the three of us met and I couldn’t help thinking …..”

I got stuck, too awkward to complete the question. But he seemed to guess, his smile broadened and his breaths grew shorter and sharper into a laugh. Now I was embarrassed.

“I’m sorry.”

“It’s alright son. I mean, me and your mum, it wasn’t like that. And if you were thinking I might be your ….” He laughed again and took a while to recover his breath. “No, I’m not.”

I looked away for a moment, grateful that nobody else could have heard, then fell into a broad smile. I felt daft, disappointed and relieved at the same time. His hand touched mine. It was a nice moment. Then he asked about me, and I spent a few minutes telling him about my wife, kids and job, and that I was content with life. He seemed pleased, but grew tired, looked upwards and his eyes closed. I said I would leave him to rest. He looked at me once more and managed a quiet word.

“Send my regards to your mother.”

“I will. What’s your proper name? I never knew.”

“Just tell her the name everyone used. I know what it was.”

Then he fell asleep.

Next day I was with Mum in her kitchen when I mentioned that I had seen him and that we had spoken. She didn’t answer immediately. Her eyes set as if she was looking inside herself and I guessed that I had touched an emotional nerve. I thought a tear was coming and touched her hand. Then she spoke.

“What exactly did he tell you?”

I thought for a moment, feeling as awkward with her as I had with him, then reckoned that now I knew the answer I could mention the question.

“He put me right on something. There was one occasion when we were together and ran into him, and I guessed you knew him, and I got a silly idea in my head.”

She looked at me as if she guessed what it was.

“I wondered if he might be …..” Again I couldn’t complete the sentence, but she nodded. “But he told me he wasn’t.”

For a moment I couldn’t tell if had offended her. I could go into an explanation about how I could understand when she had been married to my dad; but that might have made it worse. Then her expression softened and she spread her hands on the table.

“No, your dad was your dad. I had never been with another man. But I owe something to that man. Maybe both of us.”

I waited for more, but it didn’t come.

“Are you going to tell me?”

Another short silence.

“When I’m ready.”

I felt frustrated but let it go. A couple of days later she told me she had gone to the hospital, asked where he was and been told he had died during the night. A few days later she asked me to go with her to his funeral, where we paid our respects alongside three old men who looked worn out and skint and a woman from a café who had kept him fed over the past couple of years. When it was over the priest approached us and told Mum she had done something quite admirable, paying for a decent funeral after nobody had claimed the body. I had known nothing about it.

“I’ll explain one day,” she said.

That day came after another fifteen years, when she was lying in a hospital bed, both of us knowing that she didn’t have long to go. We were talking between long breaks, in and out of memories as her mind drifted. There had been a pause when she looked at me and smiled.

“I’m so glad we looked after him.”

“Who was that Mum?”

“That man who helped me. I’m glad we gave him a proper send-off.”

“I remember. The Noble Dosser.”

I returned the smile, with no intention of asking the question again. But then she continued.

“I never told you what it was about.”

“You don’t need to.”

“But you should know.”

“Mum …”

She shifted her hand onto mine and gave me a look that told me to listen.

“Your Dad went mad that night, slapped me about the kitchen and said he was going to kill me. So I hit him in the face with a saucepan, then I ran into the garden and climbed over the fence, where it came down into the bushes in the park. But it was already dark and I fell into a hole, and then I was even more scared. But then a man crouched over and pulled me out and asked me if I was alright. He took me out of bushes where he had left a shovel next to a blanket on the ground, and tried to calm me down. Then we realised your dad jumped over the fence. So the man got between us, but then your dad had him on the floor, hitting him hard, then put his hand around his throat and I could see he was going to kill him. So I picked up the shovel and hit him on the head. Then he fell over and didn’t get up again.”

My mind was knocked flat. There might have been minute’s silence but it felt like an hour. Mum broke it.

“That man sat me down and got me to drink some brandy from his bottle. Then he asked if I had any children indoors, so I said I had a little boy, and he told me to go back inside and stay quiet, and helped me climb back over the fence. An hour later he knocked on the front door, and said he had looked after everything and I should stay quiet and never tell anyone about what had happened.

“I didn’t sleep that night – my mind was all messed up – but next morning, early, I walked around to the park and he was there with some other men, all ready for a big pile of soil for a new plants. He saw me and just stood there, in a shallow hole with the shovel at his side. I went to walk towards him but he shook his head, and I realised the earth around the hole looked freshly dug, and what he had done with the body. Then they started unloading all the fresh soil and he came towards me and said you would probably be waiting for your breakfast. So I went home, and that was all.”

I didn’t speak, but I ran my hands over hers, gave it a gentle squeeze and left it there. A while later she spoke again.

“I’m sorry. I hope you don’t …”

“No Mum. You don’t need to say sorry.”

I leaned over and kissed her cheek.

The next day she slipped away for good. That was a year ago and I’m still dealing with it, shuffling through memories, feeling the waves of grief, and the Noble Dosser keeps drifting into my mind. I owe him; he made sure that I had a mum.