Claude’s heart sank as he carried the canvas towards the pond. Another picture of water lilies. It seemed like he had painted nothing else for the past ten years, slowly sinking into a task that had once been a delight, but was now a burden too lucrative to shed.

“You should feel lucky,” his agent had argued. “People love those paintings, people who are ready to pay large sums of money. Any other artist would sell his soul for this kind of success.”

“You should feel lucky,” his agent had argued. “People love those paintings, people who are ready to pay large sums of money. Any other artist would sell his soul for this kind of success.”

“Maybe that’s what I’ve done,” Claude had replied.

“Nonsense! They’re great works of art. People will delight in these pictures for centuries.”

“I would delight in never looking at another water lily again.”

“What’s wrong? Do you yearn for life in a damp, draughty garret? At your age!”

“I’ve got money.”

“And you’ve got responsibilities, a family, expensive tastes. And I’ve already accepted the commission on your behalf.”

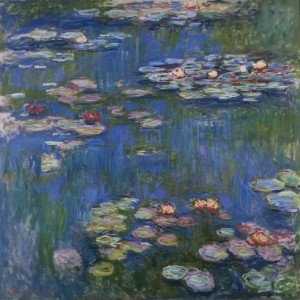

The agent had worn him down and Claude had grudgingly returned to the task. Another buyer, another perspective of water lilies, and he knew there would be more to come. He moved slowly, straining against the old man’s stiffness in his joints, and placed the canvas on the easel. Water lilies. He had painted them in all hues of green, yellow, blue, golden brown, white; resplendent in the sun, shimmering in the light of early evening, fading under raindrops. People wanted more, but always a little different to what he had done before, something with a unique quality. And everybody assumed that he was continually inspired, that it remained the obsession that had bloomed into a series of great paintings. The obsession had withered, but he had to find yet another way to show the world a bunch of bloody water lilies.

He had begun the painting the previous day but it was far from complete, so he couldn’t wander far from the original perspective. It kept him close to the easel, moving just a few feet either side to examine the pond. There was still plenty of colour on the water – summer had lingered and the flowers remained – but the cataract in his eye had grown worse and he struggled to absorb the distinctions in the light, to identify the shifts from nuance to sharp contrast. Nothing provided inspiration. He returned to the easel, sat on the stool, took up the brush, but lacked the sense of purpose to even mix the first paint on the palette. There was a faint rumble in the sky. He looked up and saw clouds, but nothing so dark as to threaten rain, let alone thunder. Maybe it was the war. Even though the fighting was far off, well beyond the other side of Paris, there were still days when the wind would carry the sound of canon fire many miles. Maybe it could reach Giverny. It depressed him further, knowing that his son Michel had endured the carnage at Verdun and would probably have to return. Maybe the world that had inspired him had gone. He sat on the chair and stared.

His vision struggled through the cloud and drifted away from the lilies onto an area of clear water. For a moment it fluttered on the surface, touching miniscule reflections of sunlight, then dived into the shimmers of green and blue to peer at its depths. Maybe he should paint what was down there, below the water lilies. He had never really looked below the surface, not with the artist’s eye, and had no creative perception of what was there. Tadpoles wriggled and emerged as frogs, some underwater foliage struggled against the sun-hugging lilies, but there was nothing that could offer excitement or delight. He persisted, pushing his gaze a little deeper into the water, disrupted momentarily by a dragon fly skipping the surface, then the faintest ripple. It created an odd perception, that the ripple had come from below rather than above the surface, and he thought he could see a small shape, almost a fingertip. It prompted him to mix a shade of blue darker than that used for the water, and dab a spot onto the canvas. It created the perception of a touch just below the surface. The thought drew him to add two miniscule lines, the curves of a finger, then another fingertip spot to its right. Someone was there.

Claude stood back, stared at the spots for a few seconds, dipped his brush and added more. A handful of restrained strokes and dabs produced another outline below the fingertips, the hint of a woman’s face. Her eyes were closed, her expression calm, almost in sleep; but the fingers on the surface conveyed an awareness of where she was, an attempt to reach out. It came without thought, but once it had taken shape he had to stand back and absorb the sight. He tried to deny the familiarity, but within moments he acknowledged that he recognised the face. It was Camille, his first wife. She had died 37 years before, still young, just months after giving birth to Michel. She had always lingered, a presence in the back of his mind, speaking rarely and showing her face less often as he grew old. He had painted her many times when she was alive, never as his life moved on, especially when Alice took her place; but now she showed herself among the water lilies. The thought disturbed him. He denied what he was seeing, insisted to himself that it was a false perception of shades in the water, dipped his brush again and placed it to the other side of the lilies. Again the process came without thought, a few gently curved lines, a few dabs, another face just below the surface. Again he stood back and stared. It was another woman, older, stronger, more assertive even in death. His second wife, Alice, always a jealous competitor with the memory of Camille, the one who stayed longer in his life but was now several years dead. She didn’t touch the surface, but he noticed a shading in the water close to her face where he had daubed a slightly darker blue. It created the shadow of a curled hand, an impression of being ready to push above the surface. Alice wasn’t happy.

Claude grew more disturbed to think of both of them in the pond, both wanting to claim him. Again he dismissed the vision, picked up the brush and found a clear spot of the water. Again the brushstrokes came without thought, a couple of indistinct lines taking shape into a mouth, a nose, eyes, a jawline. This time it was the face of a man, and Claude felt the dreadful pang that had tormented him for more than two years. It was his son Jean, the little boy he had painted several times, who had grown, married, and died shortly before the beginning of the war. Another slice of his soul that he had lost. This time he had to put down the brush, drag his chair away from the easel and sit. He didn’t want to allow any more visions of the dead to creep into the picture.

Claude dipped his head and sank under a dark wave. Two wives and a son had gone from this life, taken their place in the shadows, and now reappeared from the depths of the spot that was dominating his own life. He had complained that his agent, the buyers and the need for money had forced him into years of staring at the pond, recreating its detail from a hundred and more perspectives. He had wallowed in discontent and now realised it was mingling with grief. Camille, Jean and Alice were in there, beneath the water lilies. Maybe they had appeared because the time had come for him to join them.

His gaze returned to the pond, focusing not on the lilies but the shimmering of green and blue. He thought of touching the water, sliding a hand beneath the surface, pressing his face into his depths, allowing his body to sink. It didn’t make sense; the pond was too shallow and he knew that he wouldn’t sink without a weight pressing him down. But it felt right. Maybe the effort of breathing in beneath the surface made it possible. One large gulp to fill his lungs with water would be enough. Or maybe find some other way, deeper water, or something back in the house. Or maybe just lay down and die. He didn’t know if he could do it, but as he sat and stared he felt drawn to the thought of joining his wives and son.

It held him long enough for the shadows of the trees to shift around the pond, until it was broken by the sound of skirts hurrying through the long grass from the house. He turned to see his housekeeper approach, a worried look on her face, a grey envelope in her hand.

“A telegram Monsier Monet!”

It explained her expression; since the war began telegrams meant bad news. Claude immediately thought of Michel, realising that he could have been recalled to the front. His insides stiffened as he rose from the chair and faced the housekeeper.

“I don’t know what it is,” she said. It was typical of her, always assuring him that she behaved properly, and not at all necessary.

“Let me see.”

He took the envelope, saw no mark to indicate it was an official message, but realised that he didn’t know if there would be one if it came from the ministry or the army. He opened it, unfolded the paper and read a handful of words.

GRANTED LEAVE, ONE WEEK. HOME TOMORROW. MICHEL.

His heart fluttered. It had been just a moment of fear but the relief was immense. Tomorrow he would see his son.

“It’s from Michel,” he told the housekeeper. “He’ll be home on leave tomorrow.”

Her expression changed, sharing Claude’s relief with a suggestion that there had been no real reason for them to worry.

“Wonderful news,” she said. “I’ll prepare his room.”

She bustled back towards the house. Claude realised that she was almost as pleased as himself to see Michel, and that it was good to have her in their lives. Then he pictured Michel, in uniform but smiling at the prospect of a few days of normal life.

He turned back to face the pond. Suddenly he felt lighter, as if he had emerged from under the wave and seen the clear sky above the surface. A breeze blew, stirring the branches of the trees into a gentle dance and pushing a couple of the water lilies from shadow into the sunlight. Claude noticed how the yellow of their flowers suddenly glowed and felt that he should capture the moment. There was a painting to finish and, he admitted without shame, money to be made. But first he would have to do something about those ghostly figures in the pond.

A couple of steps to the easel, he picked up the brush then looked at the canvas. The figures had gone. There were daubs across the surface, faint changes in the water’s blue and green, but no faces or fingertips, nothing trying to emerge from the pond’s depths. Claude took just a moment to consider, wonder if he was a little mad, or losing the battle with age, then dismissed the thought. Tomorrow he would see his son, but all that mattered for the moment was the water lilies.

(So Monet painted hundreds of them; but he never repeated himself)