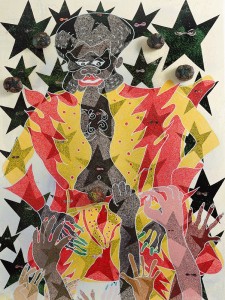

Jack stared at the painting, appreciating its flamboyant distortion of the male figure, intrigued by the jumble of hands clawing at the air, amused by the eyes peering from each of the black stars. But he couldn’t ignore the round, dark brown lumps that floated over each of the figure’s shoulders.

“So what’s with the elephant dung?” he asked.

Ellie turned her head and looked at him with a mixture of amusement and suspicion.

“I knew you’d bring that up.”

“It’s the obvious question, anyone would ask. What’s with the elephant dung?”

She looked back towards the painting.

“It’s a spiritual statement.”

“What’s spiritual about the droppings from an elephant’s arse?”

“It’s adding something raw to the canvass, straight from the natural world. It’s more basic than paint, reminds us that everything comes from the earth.”

“Even elephant dung?”

“The elephant eats what it finds in its environment, and leaves the dung when it’s finished. It’s all part of the cycle of life.”

Cycle of life. It irritated him when Ellie used words like that, made her sound like she hadn’t grown out of her art history degree. He gave it a moment, using the brief silence for effect.

“That’s arseholes.”

She looked at him. Her eyes had hardened.

“It’s a gimmick,” he went on. “A cheap trick to get the painting noticed.”

“So why did he win the Turner Prize?”

“Because they get their jollies over gimmicks.” He injected the line with a sharp shot of disdain, enough to kill any hint of a joke. “It’s the type of thing that impresses pretentious pillocks.”

“Are you calling me a pretentious pillock?”

“I never said that.”

He left a hard note in his voice and turned away before she could protest. He went to look at another painting, feeling her stare in the back of his neck.

Ten months on

Jack turned on the tap and for the hundredth time was surprised by the rattle of the pipe before the water burst into the open kettle. He had been in the flat for three months, but his mind was still conditioned by the efficient plumbing in his home with Ellie. A short burst of water was enough for the coffee, and he closed the tap with the extra twist that would prevent the dripping. The electric kettle made a noise loud enough to prompt him to turn up the hi-fi, with a hope that the woman next door wasn’t at home. He swore she must have stood with a glass to the wall, just listening for an excuse to give it a thump. The water boiled, he poured it into the cafetiere and savoured the aroma, one of the pleasures that assured him life wasn’t so bad. The phone rang. It was Ellie.

“I’ve found a buyer,” she said.

“On a Sunday?”

“They came yesterday morning and made the offer late afternoon.”

“Did you get the asking price?”

“I dropped a couple of thousand. We agreed that was acceptable.”

“That’s okay. Do they look genuine?”

“Seems so. He does something in marketing, she’s in HR for a big law firm. They’re engaged, they’re renting at the moment so there’s no chain, and they say they’ve got the OK for a big enough mortgage.”

If that was all true it was good.

“Any idea how long it will take?”

“I’ve got to talk to the solicitor, but the estate agent says it’s usually a couple of months, maybe ten weeks.”

“That’s not long.”

“I know. I’ll have to start looking for somewhere for myself.”

He heard the regret in her voice, knowing that she loved the flat and would stay if she could afford the mortgage single handed. He felt a little sorry for her, and for himself. The feeling lingered between them for a moment. Maybe they should console each other.

“We’ll have things to talk about,” he said. “Maybe we should meet up for a coffee, or lunch.”

“You’re probably right.”

“I can do today.”

There was a pause, long enough to inject a touch of tension.

“Sorry, I’m going out.”

“Meeting Susan?”

“No, someone else.”

Another pause. He realised what it meant.

“A date?”

“Yes.”

It created another awkward moment, and he had to remind himself that was OK. He had been on two blind dates himself.

“That’s good. I’ll be in touch.”

The call left him restless. They had gone through their long conversations, shed some tears, and agreed they were no longer right for each other, and she had as much right as he to get on with her life. But it stung. It didn’t help that he had nothing to do that day, so after a couple of hours sulking on the sofa he dragged himself towards the river, crossed Lambeth Bridge and ambled westwards. Then he found himself at the gallery and saw the poster outside: one big exhibition for the elephant dung man. He thought of that afternoon, one of the moments when things became a little worse for them, and his first instinct was to turn away. Then he flipped the idea, thinking that the paintings would remind him of why Ellie had been wrong for him.

Ten minutes later he stared at a lump of elephant dung. It still irritated him, but details of the painting stirred a moment of pleasure, a squint in the woman’s eyes, her softly curved lips, the vibrancy of the primary colours swirling from her face. He walked on, and found himself lingering over some of the paintings, his mind temporarily detached from all that had gone wrong. It was the last room that was most striking, a collection of large canvasses with sleek bright lines upon dark blue and black, portraying figures full of elegance and energy. He stood in front of a picture of a couple dancing amid palm trees and acknowledged to himself that the artist was a class act, someone who could convey the magic in people’s lives. Ellie would have liked this.

Then he was flattened by a crushing sadness, knowing that the pleasure was dulled, and would be for a long time, by not being able to share it with her. And it was his own fault.

Four months on

Ellie answered the door with a neutral expression and stepped back before he could offer a kiss. It was what he had expected, another tiny reminder that they were past affection, and he followed her into the flat at a respectful couple of paces, hearing the TV in the background.

“Where did you find it?” he asked.

“At the back of the cupboard. Somehow it got behind the laundry basket.”

“I can’t remember placing it there.”

“Maybe you placed it on top.”

He thought it more likely that she had placed it there during one of her cleaning binges, but decided there was no point in saying so. She led him into the kitchen where it stood in front of the washing machine, a Powell Peralta skateboard with a skull under a Viking helmet, a treasured possession of his teenage years that he had never been ready to give away. He looked it over and felt pleased.

“I reckon this is worth a bit on eBay now.”

“Is that what you’re going to do with it?”

“No way. I’ll keep it.”

“At the back of another cupboard?”

“Maybe I’ll hang it on the wall.”

He wouldn’t, but he noticed the remark drew a little twitch of her mouth. She offered a coffee, he accepted, they sat in the lounge with the TV on low volume and began to talk about their slap in the face. The buyers had delayed exchanging contracts on the flat for three weeks beyond the original date, then admitted that the guy had lost his job and couldn’t go through with the purchase. They were back to square one on the sale, minus more than a thousand pounds in solicitor’s fees. He asked if the estate agent had put it up for sale again.

“No,” said Ellie. “I told them to put it on hold for a while.”

“Why? I thought you wanted out of here.”

“I do, I did, but …. I got so wound up by the sale falling apart. I lost sleep, cried a lot.”

There was a shift in her expression, almost asking for sympathy.

“I understand,” he said. “I worried about it, and you’re living here so it must have been worse. You need a little time.”

“That’s good of you.”

“But I can’t handle it for too long. And within a few months I’ll need my share of the profit from the sale.”

“You’re right. Maybe a month or so.”

He drew a quiet breath, making a quick financial calculation, silently winced then reminded himself he couldn’t take another quick sale for granted.

“Okay. We’ll talk about it again in a month.”

“Thanks. You’re sweet.”

She showed a grateful smile. He was still thinking of the money, but also feeling this was one of those moments in life to be generous, for himself as much as Ellie. He sipped at the coffee and asked if she was getting out much.

“A little.”

“Dating?”

“A couple of times. Hasn’t come to anything. What about you?”

“Haven’t been in the mood.”

It left them in an awkward silence, a recognition that neither was happy with the turns their lives had taken, but that they were past the point of sharing their emotions. The only sound came from the TV, a newsreader telling them of the latest woes in the world. There was something about a flood in northern Spain, then a story about the French foreign minister being ambushed by environmental activists.

“They were protesting against the government’s support for a French company’s bid to gain mining rights in one of Kenya’s national parks, and chose an unusual means of making their point. Elephant dung.”

Jack and Ellie both looked towards the screen to see a man in a suit hit by large brown lumps from slingshots in a small crowd. One caught him in the face, and the camera lingered as he dug into his pocket for a handkerchief and tried, unsuccessfully, to wipe himself clean.

“Shit!” said Jack.

“You’re right,” said Ellie. “That’s what it is.”

They chuckled as security men hustled the minister back into the building, one of them squeezing his own nose.

“I suppose that was a spiritual statement,” said Jack.

Ellie looked at him. He froze. He had just reminded her of their bad moments, and her eyes showed that she remembered every detail. It was a couple of seconds before she replied.

“Yeah, something raw, straight from the natural world. They’ve just reminded him that everything comes from the earth.”

Her mouth twisted, halfway to a smile. Jack took a chance on a chuckle. Then they both laughed, loud enough for relief to fill the room.

Three weeks on

They stood in front of the same painting as before. Jack felt shamed by the memory of his sneering, stared at the elephant dung and hesitated to look at Ellie. He knew that she was running her mind over the same memory, and it lasted for the best part of a minute before her head turned.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “I’m not going to say anything about spirituality or cycles of life.”

“You just did.”

She punched his arm. They both smiled.

“It is good though,” he said, “with or without the elephant dung.”

“I’m glad you think so.”

“And I’m sorry about last time. I acted like an unpleasant dickhead.”

“Yeah, you did, but saying so is the second part of redeeming yourself.”

“Thanks.”

They kept their eyes on each other and shuffled their feet uncertainly as if there was something to stop them moving on. She tightened her mouth a little and he knew it was the moment to ask.

“I’ve been thinking,” said Jack. “Do you think it might work if I moved back in?”

“It might.”

“So we can try again?”

“We can try again.”

They waited a second, then threw their arms around each other and pressed their lips together, long and hard enough to prompt everyone nearby to move away. When they let go they gently bumped noses and gave each other big time smiles. Then they strolled to the next gallery hand in hand.