Jack held the door open for Peggy to enter the diner. They walked the length of the counter so they could sit at the far end and face towards the door. The fluorescent strips on the ceiling cast a harsh light over the room, reducing everything through the window to shadows, and Jack could see no sign of the guy. After a few seconds he gland Peggy glanced at each other to register their relief. It was only then that he noticed it wasn’t the usual waiter, but a younger guy with blond hair and an unfamiliar smile.

“What can I do for ya?” he asked.

“What can I do for ya?” he asked.

“Coffee,” replied Peggy.

“Same for me,” said Jack.

The waiter turned, took two small mugs from a shelf beneath the counter and pushed one beneath the tap of the coffee urn. It ejected a faint hiss and Jack felt Peggy squeeze his hand. They had been both been scared.

“We’re seeing spooks,” he said quietly. “That guy was nothing.”

“I know,” she replied.

The waiter placed the mugs in front of them.

“Black or white?”

“Black,” said Jack.

“I’ll have a splash of milk,” said Peggy.

The waiter took the milk jug, and as he poured the diner door opened and the guy walked in. They hadn’t seen his face in the street but knew it was the same guy, shorter than Jack, stocky, the brim of his hat tilted down. Jack felt Peggy squeeze his hand again, this time tighter, but kept his eyes forward. His heart beat hard as the guy walked the length of the counter and sat on the stool before its corner. From there he could look straight ahead and keep them in his field of vision.

“Coffee please,” he said.

“Coffee it is,” the waiter replied.

Jack gently loosened Peggy’s hand. The squeeze was an indication of fear, an admission of guilt. He glanced at her and mumbled, too quietly for any other ears: “Stay calm.”

“Black or white?” asked the waited.

“Black,” said the guy.

The waiter placed the mug on the counter. The guy took a spoon, looked down at the mug and stirred slowly. Jack watched from the corner of his eye, suppressing the urge to acknowledge his fear. He looked forward, took a packet of smokes from his side pocket and removed one slowly, assuring himself that his hand was steady. He offered the cigarette to Peggy. They shared a silent question. Did her husband send this guy? She shook her head to the cigarette, but her eyes said she didn’t know the answer to the question. Jack lit up and took a long draw on the smoke. It steadied him, enough to feel confident in pretending there was no reason to be scared. A glance told him the guy was still looking into his coffee mug, the hat brim tilted just enough to conceal his eyes. Jack leaned forward on the counter. Peggy followed his lead and raised a hand to inspect her fingernails. That’s good, he thought. Do what a woman would do when there’s nothing on her mind.

Jack decided it would help to make small talk with the waiter.

“Where’s the regular guy?” he asked.

“Regular guy?”

“The one who usually does the graveyard shift.”

“He’s sick. Boss asked me to cover.”

“You doing a double shift?”

“Nah, we juggled them.”

“Must be difficult, working this late.”

“I’ve done it before. Like it. You don’t often find it this peaceful in here.”

The other guy lifted his head and spoke.

“You like it this way?”

“Yeah,” said the waiter. “Tends to be busy enough over the whole shift, but there are always quiet times, when I can think about things.”

“You got a lot to think about?”

“Enough, mainly to do with keeping my girl happy, but not so much to keep me asleep at night.”

“I hope she’s not hard to keep happy.”

“Nah, she’s good to me.”

“That’s good.”

The smiled, first at the waiter, then at Jack and Peggy. He seemed friendly, the type who liked conversation with strangers. Jack was still wary but thought it better to acknowledge the smile.

“Working late?” he asked.

“Could say that,” said the guy. “I was due to meet a guy but he wasn’t there. I found a phonebox, he promised he was coming, I had time for a coffee.”

“So you came here.”

“I came here, at this time of night. Couldn’t have done that when we were kids, found a diner open for a coffee this late.”

“That’s progress.”

“What about you? Working?”

Jack glanced at Peggy. She shuffled a little in her chair, a faint giveaway.

“Been working,” he said. “Had to stay late.”

Peggy joined in the lie.

“We deal with people on the west coast, and they deal with people in Hawaii. Sometimes something happens and we have to stay real late.”

“That’s dedication,” said the guy.

“It’s what you do to keep your job.”

There was a sing song cynicism in Peggy’s voice, one of the things he liked about her, one of the reasons for risking what her husband might do.

“So what’s the business?” asked the guy.

“Shipping,” said Jack. “Routine stuff, but it brings in the money.”

“That’s what it’s about.”

“You’re right, that’s what it’s about.”

The guy sipped at his coffee and they sat in silence. Jack smoked his cigarette, Peggy examined her fingernails, and the waiter began to rearrange dishes under the counter. Jack kept his eyes off the other guy, but felt a little easier. For a couple of minutes they just sat still as quiet creatures of the night.

Then the other guy looked at his watch, took a last mouthful of coffee and placed a couple of coins on the counter.

“That’s it,” he said. “All good.”

The waiter nodded to him.

“G’night mister.”

As the guy left the diner he looked back at Jack and Peggy.

“Goodnight folks.”

They returned the goodnight, and as the guy stepped outside they looked at each other and shared a long, outward breath of relief. Their faces relaxed into faint smiles and their heartbeats became less intense. They didn’t need to tell each other that this had gone on for long enough, that the tension between their longing for each other and the fear was too much to sustain. Soon they had to take off to some place her husband would never find them. They clasped hands and smiled into each other’s eyes. Then Jack realised the waiter was facing them across the counter. He said four words.

“The guy said ‘all good’.”

He slapped one hand around Jack’s neck and with the other pulled a large knife from beneath the counter. A single lunge took it into Jack’s chest, beneath the left rib cage and up to pierce his heart. The waiter released the body, and as Peggy screamed he grabbed her hair and ran the blade across her throat. Both bodies went backwards, crashing from stools to the floor and leaking dark pools of blood. The waiter walked around the counter and looked down. Jack’s eyes were already cold. Peggy gagged for a few seconds then closed her eyes for ever. In the corner the diner door opened and the other guy returned. He took a gun from his pocket, walked around the counter and looked down on the bodies.

“Both dead,” said the waiter. “No need for a bullet.”

“That’s better,” said the guy.

“I told you I could do it quiet.”

“Okay. Where’s the other guy? The one who works here.”

“Out back, unconscious, tied up, gagged.”

“Pistol whipped?”

“No, chloroform. He’ll wake up in two, three hours. I’ll untie him before then, we’ll be gone. He won’t even know what happened.”

“That’s good. My other guy’s in the car. We’ll get these out of here, then you clean up.”

“If I’m interrupted?”

“Somebody broke a glass and cut their hand. They’ve gone to the hospital. But you’d better put the closed sign on the window. Just change it back when you leave.”

The waiter looked down at the bodies.

“What about when someone comes looking for them?”

“They were never here.”

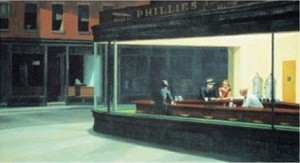

(From Edward Hopper’s iconic painting; this one was asking to be written.)